|

Size: 12226

Comment: equivalent command for git describe

|

Size: 12375

Comment: git checkout inserted

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 142: | Line 142: |

| ||`git checkout <commit>` ||`hg update -C <cset>` || by default, git ensures that all files equal commit state (e.g. removed files are restored) || |

Mercurial for Git users

Git is a very popular DistributedSCM that works very similar to Mercurial. However, there are some design and conceptual differences that may cause trouble when coming from Git to Mercurial.

Contents

1. Logical architecture

Mercurial and Git differ only in nomenclature and interface. Git tends to expose more concepts to the user, but gives hints to the user what command might make sense next.

Mercurial has always focused more on interface aspects, which made it originally easier to learn. In comparison to Git, a shallower understanding is required to operate with Mercurial in a useful manner. In the long run, such encapsulation has given Mercurial the false appearance of being less powerful and featureful than it really is.

This section tries to prove that the only logical architecture difference between the two systems, is nomenclature.

1.1. History model

One of the first Git lessons is the repository basic object types: blob, tree and commit. These are the building blocks for the history model. Mercurial also builds up history upon the same three concepts, respectively: file, manifest and changeset.

To identify these objects both systems use a SHA1 hash value, what Mercurial calls nodeid. Additionally, Mercurial also provides a local increasing number for each changeset instead of the reverse count notation provided by Git (like HEAD~4).

From that, Mercurial's view of history is, just like Git's, a DAG or Directed Acyclic Graph of changesets. For instance, the graphical representation of history is the same in the two.

1.2. Branch model

Also like in Git, Mercurial supports branching in different ways. First and foremost, each clone of a repository represents a branch, potentially identical to other clones of the same repositories. This way of branching is sometimes referred to as heavy branches and works almost the same in both systems.

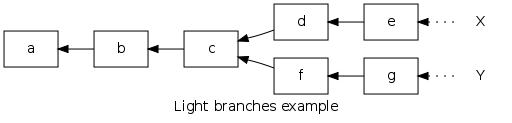

Then Git has its famous lightweight branches, which allow switching between development lines within the same clone of a repository. Take the following history graph as an example:

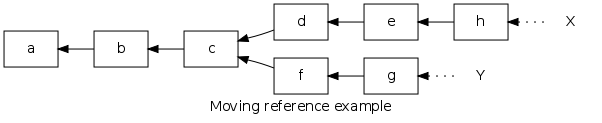

In Git, branches X and Y are simply references to the e and g commits. If a new commit is appended to e then the reference X would point to such commit, like this:

Mercurial has always supported these kind of branches, but with a different name and in a somehow anonymous way. In Mercurial, the X and Y branches are called heads and, until recently, they had to be referred by their changeset identifier: either local (number) or global (SHA1 hash). In brief, it is like using Git detached heads instead of branch names, but much easier (see hg help heads).

Since Mercurial 1.2, the BookmarksExtension provides a way to identify and follow a lightweight branch with a symbolic name, similar to Git. Bookmarks are local, contrary to Git's branches.

Keep in mind that bookmarks do not propagate over clones, pulls nor pushes because they are not part of the history data nor reflected on the WireProtocol. (But they could be transferred (using ssh, for instance) and bookmarks would work fine, as they point to changeset global identifiers.)

Keep in mind that bookmarks do not propagate over clones, pulls nor pushes because they are not part of the history data nor reflected on the WireProtocol. (But they could be transferred (using ssh, for instance) and bookmarks would work fine, as they point to changeset global identifiers.)

Finally, Mercurial has another branching functionality called NamedBranches, also known as long lived branches. This kind of branch does not have a Git equivalent. For more information about named branches:

1.3. Tag model

Like with branches both Git and Mercurial support two tag levels: local and global. Local tags are only visible where they were created and do not propagate, so they behave practically the same in both systems.

Global tags is one of the aspects that really differs from Git. Apparently they serve the same purpose, however they are treated differently. In Git, global tags have a dedicated repository object type; these tags are usually referred as annotated tags. In Mercurial, though, they are stored in a special text file called .hgtags residing in the root directory of a repository clone. Because the .hgtags file is versioned as a normal file, all the file modifications are stored as part of the repository history.

Two important things need to be remembered about how .hgtags is handled:

- The file only grows and should not be edited, except when it (rarely) generates a merge conflict.

Because it is revision controlled, there is a corresponding revlog. When looking for tags, only the latest revision of .hgtags is parsed; never mind the checked out copy revision.

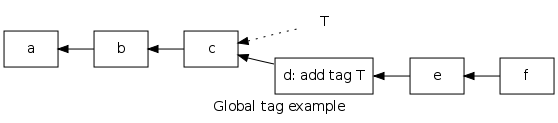

Although it is questioned by many people new to Mercurial, this design allows to keep track of all global tagging operations. Nevertheless, it also confuses many Mercurial newcomers because it can lead to some puzzling scenarios. For example, consider the following history graph:

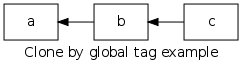

In the graph, T is a global tag pointing to changeset c. This tagging action generated changeset d because .hgtags had to be committed. Now, if you clone a new repository using hg clone --rev T, the history graph of the cloned repository would look like this:

Therefore, in the new repository tag T does not exist. The reason behind this is because in the original repository tag T points to changeset c; however, tag T is added by commit d which is a descendant of c. As the clone command limits the history up to changeset c, the addition of the tag is not included in the new repository. Things work similarly when tagging a particular revision using hg tag --rev ...

Regarding tag propagation across repositories, Mercurial has very simple semantics. From the history and WireProtocol point of view, the .hgtags file is treated like the rest of the tracked files, which means that any global tagging operation becomes visible to everyone just like any other commit. It also implies that merge conflicts can occur in .hgtags.

The rationale behind Mercurial's global tags is briefly justified in this thread (January 2009).

See also: Giving a persistent name to a revision.

2. Behavioral differences

In most design decisions, Mercurial tries to avoid exposing excessive complexity to the user. This can sometimes lead to the belief that both systems have nothing in common when in practice the difference is subtle, and vice versa.

2.1. Communication between repositories

It has already been explained how similar the branching model is in both Git and Mercurial. When it comes to moving history between different repositories, the behaviour is slightly mismatched.

Git adds the notion of tracking branch, a branch that is used to follow changes from another repository. Tracking branches allow to selectively pull or push branches from or to a remote repository.

Mercurial keeps things simpler in this aspect: when you pull, you bring all remote heads into your local repository. Then you can decide whether to merge or not. Or else, pull and merge automatically using the FetchExtension. While this scheme may seem more rigid, it actually helps maintaining cleaner public repositories. Following the same rationale, all pushes that would create new heads (i.e. lightweight branches) stop with a warning, except if the user explicitly forces them.

Remember also that bookmarks do not propagate over pushes nor pulls. (But they could be transferred (using ssh, for instance) and bookmarks would work fine, as they point to changeset global identifiers.)

2.2. Git's staging area

Git is the only DistributedSCM that exposes the concept of index or staging area. The others may implement and hide it, but in no other case is the user aware or has to deal with it.

Mercurial's rough equivalent is the DirState, which controls working copy status information to determine the files to be included in the next commit. But in any case, this file is handled automatically. Additionally, it is possible to be more selective at commit time either by specifying the files you want to commit on the command line or by using the RecordExtension.

If you felt uncomfortable dealing with Git's index, you are switching for the better. ![]()

2.3. Bare repositories

Although this is a minor issue, Mercurial can obviously handle a bare repository; that is, a repository without a working copy. In Git you need a configuration option for that, whereas in Hg you only need to check out the null revision, like this:

hg update null

As push and pull operations do not update the working copy by default, by not updating the working copy you get the same effect of a bare repository. In fact, it is the recommended option for some particular hgwebdir.cgi setups.

3. Command equivalence table

The table presented below is far from being complete due to the large amount of command and switch combinations that Git offers. Nevertheless, it tries to cover the most shocking changes when moving from Git to Hg:

Git command |

Hg command |

Notes |

git pull |

hg fetch |

Requires the FetchExtension to be enabled. |

git fetch |

hg pull |

|

git checkout <commit> |

hg update -C <cset> |

by default, git ensures that all files equal commit state (e.g. removed files are restored) |

git reset --hard |

hg revert -a --no-backup |

|

git revert <commit> |

hg backout <cset> |

|

git add <new_file> |

hg add <new_file> |

Only equivalent when <new_file> is not tracked. |

git add <file> |

— |

Not necessary in Mercurial. |

git add -i |

hg record |

Requires the RecordExtension to be enabled. |

git commit --amend |

hg qimport -r tip ; hg qrefresh -e ; hg qfinish tip |

Requires the MqExtension. |

git blame |

hg blame or hg annotate |

|

git bisect |

hg bisect |

|

git rebase --interactive |

hg histedit <base cset> |

Requires the HisteditExtension. |

git stash |

hg shelve |

Requires the ShelveExtension or the AtticExtension. |

git merge |

hg merge |

|

git cherry-pick <commit> |

hg transplant <cset> or hg export <cset> | hg import - |

Transplant requires the TransplantExtension. |

git rebase <upstream> |

hg rebase -d <cset> |

Requires the RebaseExtension. |

git format-patch <commits> and git send-mail |

hg email -r <csets> |

Requires the PatchbombExtension. |

git am <mbox> |

hg mimport -m <mbox> |

Requires the MboxExtension and the MqExtension. Imports patches to mq. |

git describe |

hg tip --template '{latesttag}-{latesttagdistance}-{node|short}\n' |

|

git describe rev |

hg log -r rev --template '{latesttag}-{latesttagdistance}-{node|short}\n' |

|

While git has an output of the commands one could use next, hg does this only in rare cases.